From Assembly to AI: Why 'Vibe Coding' Is Just Another Chapter in Our Abstraction Story

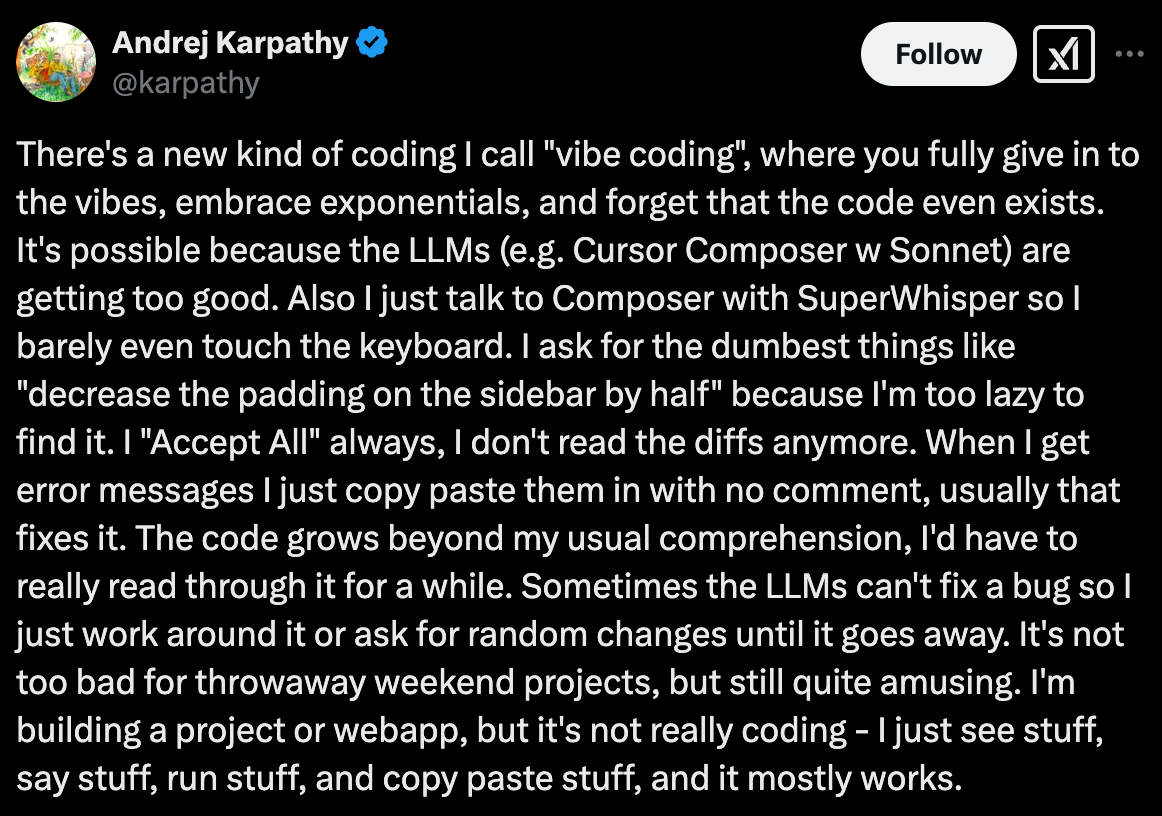

Two days ago, Andrej Karpathy set Tech Twitter ablaze with a provocative idea he calls "vibe coding" – where you "fully give in to the vibes, embrace exponentials, and forget that the code even exists." Using AI tools (like Cline), he demonstrated building an entire LLM reader application in about an hour, barely touching the keyboard.

The reactions were predictable and eerily familiar to anyone who knows their computing history. But to understand why, we need to go back. Way back.

What is 'abstraction' anyway? Abstraction is hiding complexity behind simpler interfaces. When you drive a car, you don't think about the engine – you just use the steering wheel and pedals. Each new layer of abstraction in computing follows this same pattern, letting us focus on solving problems rather than managing details.

The Assembly Wars (1950s)

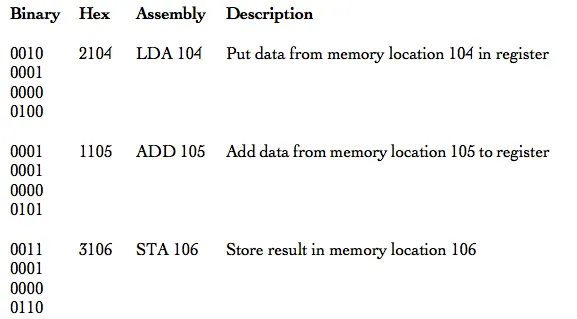

In the beginning, there was machine code – raw 1s and 0s fed directly to the processor. When assembly language was introduced in the 1950s, offering human-readable mnemonics instead of binary, many programmers were outraged. They argued that abstracting away from direct machine instructions would lead to inefficient code and a loss of understanding.

Sound familiar?

The FORTRAN Revolution (1957)

Then came FORTRAN. John Backus, tired of writing complex mathematical computations in assembly, created what we now call the first high-level programming language. His motivation? As he put it: "Much of my work has come from being lazy. I didn't like writing programs."

The resistance was fierce. Many programmers doubted a compiler could ever match hand-coded assembly's efficiency. They were wrong. FORTRAN not only matched assembly's performance – it made programming accessible to scientists and engineers who didn't want to think in machine instructions.

The Unix Moment (1973)

But perhaps the most relevant historical parallel to today's "vibe coding" debate happened in 1973. Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson decided to rewrite Unix in a new language called C. The idea of writing an entire operating system in a high-level language was considered absurd.

Critics argued:

- It would be too slow

- You'd lose control over the hardware

- The added complexity would make the system unmaintainable

Instead, C's abstraction of machine details enabled Unix to become one of the most portable and influential operating systems ever created. As Thompson later noted: "Unix is very simple, it just needs a genius to understand its simplicity."

The Pattern Emerges

Look at these historical moments, and a clear pattern emerges:

- New abstraction is introduced

- Veterans resist, citing loss of control

- Early adopters embrace it

- The abstraction proves its worth

- It becomes the new normal

- Repeat

This pattern has played out repeatedly:

- Assembly → "But what about machine control?"

- C → "Too slow, need assembly"

- Python → "Real engineers use C++"

- React → "Just write vanilla JS"

- AI → "You won't understand the code"

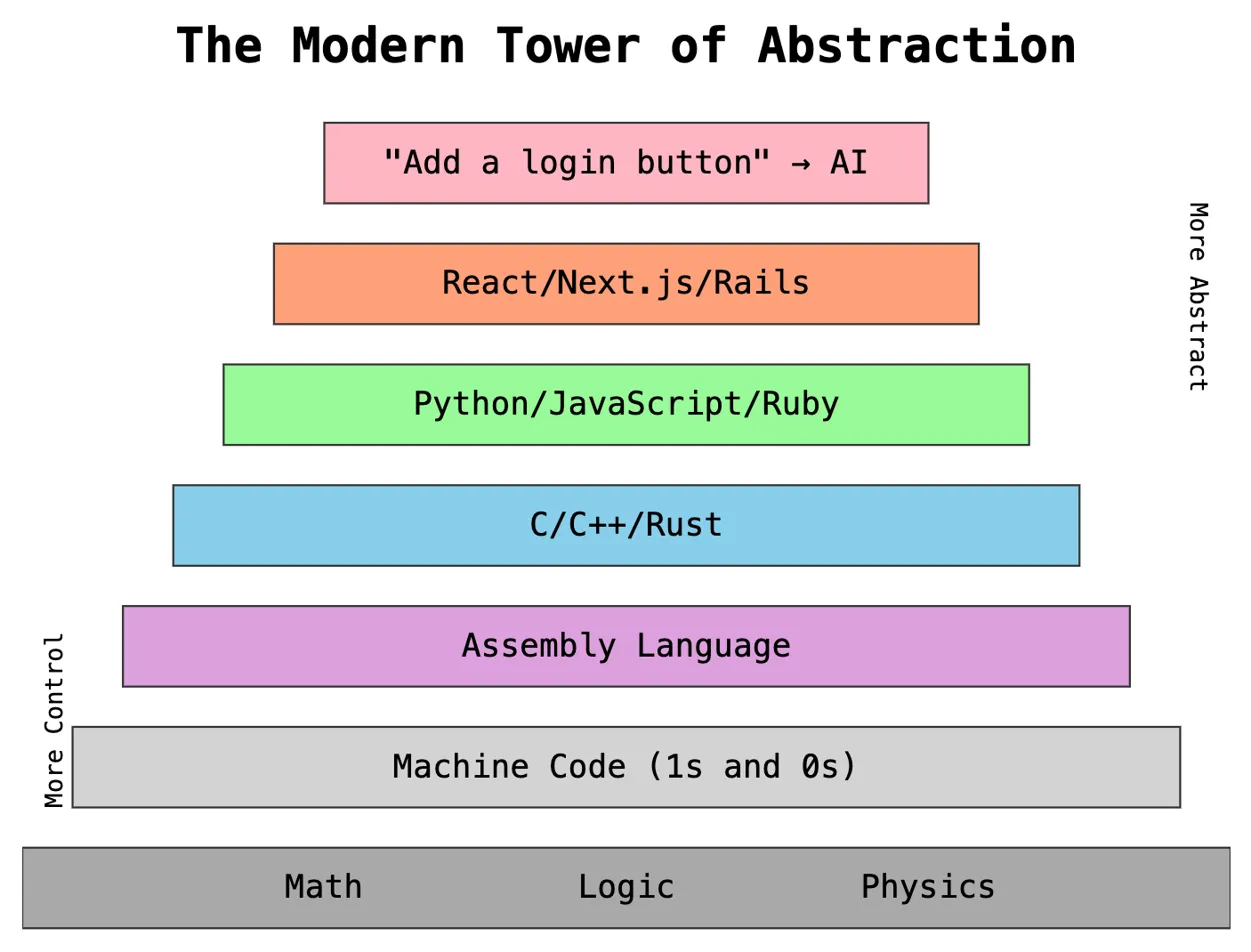

The Modern Tower

What I call the "Modern Tower of Abstraction" illustrates how far we've come. Each layer solved specific problems:

- Assembly freed us from binary

- C gave us portability

- High-level languages automated memory management

- Frameworks standardized patterns

- And now, AI promises to abstract away implementation details entirely

But here's what makes "vibe coding" fascinating: it's not just another layer – it might be a fundamental shift in how we express intent to computers. Instead of telling machines exactly what to do through precise instructions, we're moving toward describing what we want in natural language.

Not Everyone Believes in AI as an Abstraction

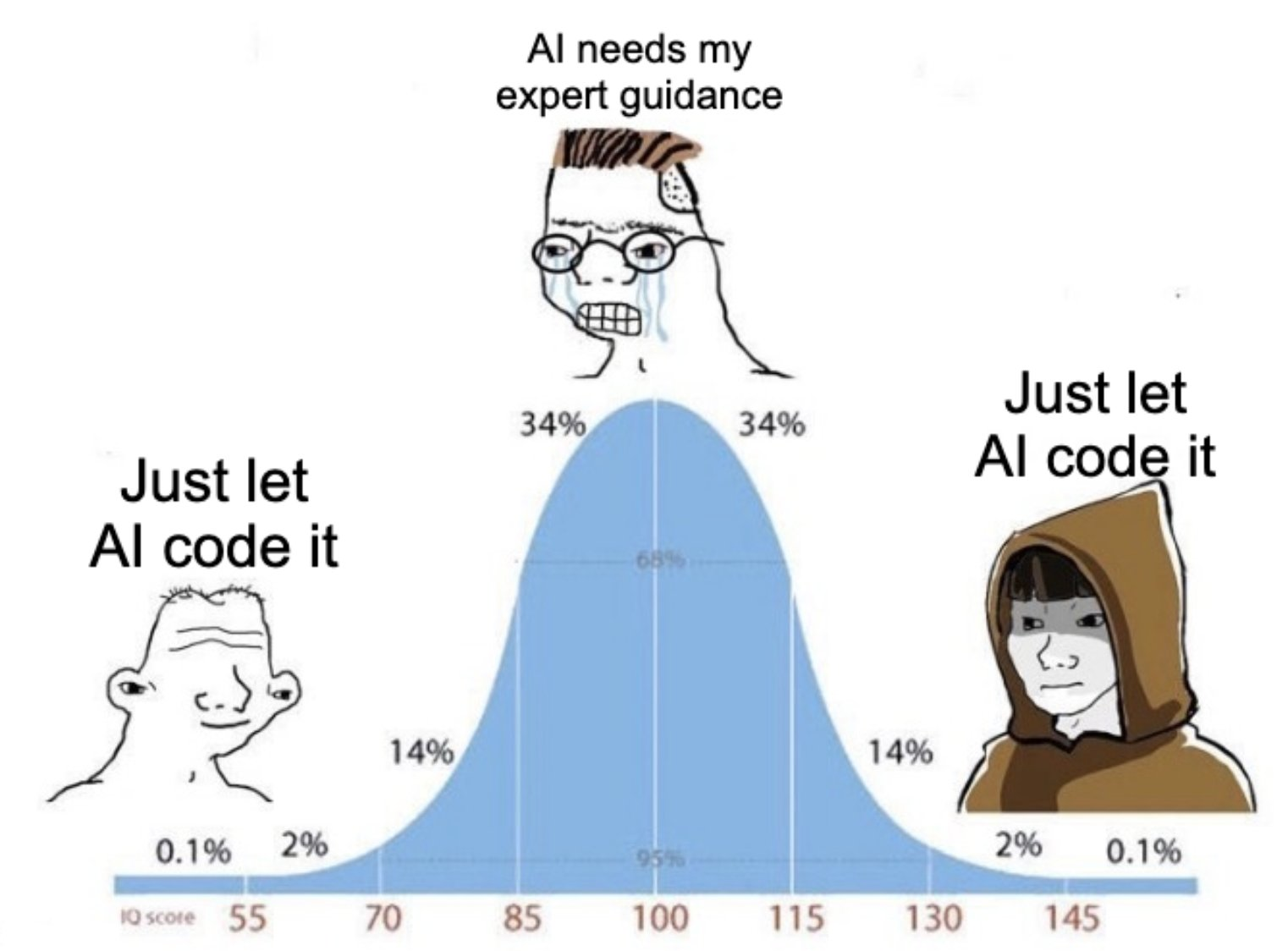

The bell curve meme circulating with Karpathy's announcement captures something fascinating about developer attitudes. At both ends of the curve, you find the same conclusion ("just let AI code it") but reached through entirely different paths. Those with lower expertise embrace it out of naive optimism, while those with the highest expertise embrace it through deep understanding of abstraction layers. And in the middle? The cautious skeptics insisting "AI needs my expert guidance" – perhaps missing that both complete resistance and complete embrace are part of the same cycle we've seen before.

Finding the Balance

At Cline, we recognize this historical pattern. Just as C didn't eliminate assembly language but made it unnecessary for most tasks, AI won't eliminate traditional coding but will change where we spend our cognitive effort.

Our approach provides a human-in-the-loop experience where developers can:

- Express intent in natural language

- Review and approve AI-suggested changes

- Maintain control while gaining speed

- Drop down to lower abstraction levels when needed

The Road Ahead

"Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute," wrote Harold Abelson. This principle remains true even as we add new layers of abstraction. The goal isn't to eliminate complexity but to manage it more effectively.

Whether "vibe coding" becomes as fundamental as previous abstractions remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: those who dismiss it entirely are echoing the assembly programmers of 1957, the systems programmers of 1973, and every other group that resisted a new abstraction layer that ultimately became standard.

The future of development isn't about choosing between extremes – it's about understanding which level of abstraction is appropriate for each task. Sometimes that might mean going full vibe mode. Other times it means diving deep into the implementation. The key is having the tools and wisdom to know the difference.

This blog was written by Nick Baumann, Product Marketing at Cline. Follow us @cline for more insights into the future of development.